A Win-Win Approach to Conflict Resolution and Potential Power Struggles Among Learners or Students.

A Win-Win Approach to Conflict Resolution and Potential Power Struggles Among Learners or Students.

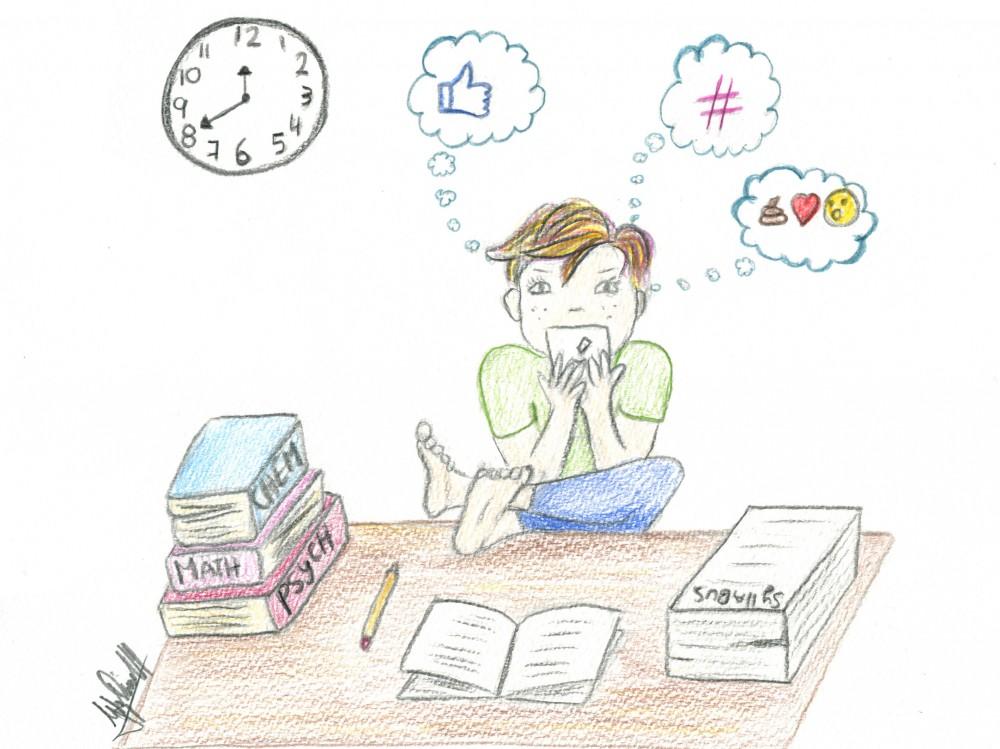

Conflict is a natural part of any functional classroom setting.

It is not necessarily a sign of problems with classroom management or the health of the classroom community.

But it can often lead to unhappiness or discomfort, and some members of the class may emotionally withdraw or attack.

Making sense of conflict and providing students with the skills, knowledge, and dispositions to process it effectively is essential to creating a functional democratic classroom.

Sources Of Conflict

- Conflict originates from many sources and takes many forms.

- Sometimes it is brought into the class from the outside, and sometimes it is created within the class.

- Either way, when examined with sufficient awareness, it can be a useful means to personal and collective growth.

- Our job is to help students see that conflict can be an opportunity rather than just a source of grief.

- This article looks at the most common sources of classroom conflict.

- Students Have Competing Ideas

- As you develop a culture of listening and respect, you have to help students separate differences of opinion from personal attack.

- Helping them learn the skills of self-expression while keeping the dignity and respect of others paramount is important.

- It can be useful to illuminate for students the concept that their ideas have changed over time and will undoubtedly change in the future.

- As they better distinguish their ideas from their identities, they will find it much easier to have discussions without getting defensive.

- You can allow students to disagree and permit them time to process those emotions.

- As they learn that not always being right or having others disagree is not the end of the world, they become more comfortable with self-expression and less fearful of conflict

- In addition, you need to help students express their ideas in ways that do not attack others.

- A good way to start is to help them use phrasing that identifies their idea as their opinion.

Students Have Competing Needs and Desires

No matter how clear your expectations, no matter how well understood your social contract, and no matter how well you promote community among the members of the class, there will be some level of conflict that comes from students’ competing needs and desires.

But the difference between a democratic classroom with an intentional process for dealing with conflict and an authoritarian classroom where the teacher acts as judge is this:

- In a democratic classroom, conflict is an opportunity for all parties to grow, while in an authoritarian classroom, conflict is a source of trouble for all concerned.

- Moreover, in a democratic classroom, each conflict leads to more learning and skill building, which leads to more effective conflict resolution and less future pain and suffering.

- Teacher-based resolutions lead to dependent and passive students who learn little about how to deal with the conflicts that arise in their lives, in or out of the classroom.

Avoid these actions concerning conflict between students:

Ignoring conflict.

- This leads to the benefit of the advantaged.

- The powerful will ultimately use the vacuum of justice to get their way over the less powerful.

Acting as judge.

- This sends the message that students are too immature to solve their problems and impedes their moral and social growth.

Siding solely with the victim.

- Be empathetic, but avoid being used as a tool to get back at an aggressor.

- This will lead to more dependence and a cycle of victimization for the weak party and an identity as a bully for the aggressor.

Don’t encourage tattling.

- The more you encourage it, the more you will get it.

- You encourage it by acting as a judge, siding with the victim, or not encouraging students to seek their solutions before they come to you.

Encourage the following actions concerning conflict between students:

- Use of a well-established set of guidelines for conflict resolution. An effective and uniform system helps support a sense of safety and learning for students

- Skills related to expressing and owning one’s feelings. Empathy is a complex skill to learn, but effective and saves a lot of pain and suffering.

- An effort on the part of the students. They should ask themselves, “What is the best thing for the class as a whole, and can I find a solution that meets my needs and is good for the group as well?”

- An inclination to solve one’s conflict. It may feel difficult not to intervene at first, but you will be surprised at how empowering it can be for the students, especially those who have previously been dependent on adult interventions.

- An inclination to think in terms of one’s behavior first and that of others second. Too often, conflicts escalate because students all feel the need to point out the misbehavior of other students.

- An effort to recognize how much they are growing in their conflict resolution skills. As with the other skills that you are trying to encourage, do not hold back your pride and respect for students who are making the effort to grow in a new and difficult area.

- If a conflict or series of conflicts sends the message that something is not working, use the opportunity to brainstorm a contract modification. This activity can be a conspicuous opportunity to model the principle that conflict is an opportunity for growth.

Teacher’s Negative Affect or Misguided Practice May Lead to Student Conflict

- This may take the form of resistance stemming from a feeling that basic needs are not being met.

- It may take the form of jealousy if you use extrinsic rewards or personal praise.

- It may take the form of mistrust if you are inconsistent with your consequences or use arbitrary punishments.

- In one form or another, student discomfort will lead to conflict

- Create a safe, needs-satisfying, consistent classroom climate, and you will have to do a lot less conflict resolution and power struggle management.

Students’ and Teachers’ Needs Compete

- Even if you are successful at creating a healthy needs-satisfying classroom where expectations are clear, there are bound to be times when your needs and those of your students will be at odds.

- Sometimes, just explaining the rationale behind your expectations can help students see why they are necessary.

- Sometimes it may be necessary to engage in a process of problem-solving to achieve understanding.

For instance, you may have a homework policy that seems to make perfect sense, but several students do not complete most or all of their homework.

- In situations like this, it is important that you listen to your students’ needs.

- Ask what they would change in the policy to ensure that everyone comes with their homework completed.

- After listening to suggestions, you can find a practicable compromise that works for all parties.

- Bluestein (1999) calls this negotiating “creating a boundary.”

- She suggests that conflict is minimized when each party can accept a policy boundary that works for him or her.

- This process helps meet the students’ basic need for power and brings another level of clarity to the expectations.

Students Bring Displaced Anger from Outside the Class

- Sometimes you have done a good job of developing a sound policy and a fair and supportive classroom environment.

- But because one or more students feel the need to test you or “share their pain,” potential conflict can arise.

A System for Win-Win Conflict Resolution

Having a system for conflict resolution in place for your classroom or school can have many benefits.

- First, it will reduce the amount and intensity of the conflict that does occur.

- Second, it will help students build useful skills to solve their problems; skills that will be valuable within the school walls and in their homes and communities.

- Third, the conflict resolution skills will act to promote a deeper sense of responsibility, community, and success psychology among the student body.

Naomi Drew (2002) offers a six-step process for successful conflict resolution. It can be used by students for self-mediation or by a peer mediator.

These steps provide a useful framework for examining how to make a conflict an opportunity for growth rather than disharmony.

1. Cool Off

- Drew (2002) suggests that conflict cannot be solved in the face of hot emotions.

- It is important for all parties within any conflict to take a step back and recognize the reactive pattern that wants to emerge and gain some distance and perspective.

- Help students develop the habit of taking a moment to turn their attention inward and notice that they most likely want to react out of a pain-based response whenever they feel they have been hurt, threatened, or wronged.

- The pain-body reaction blinds us to reason and incites more pain in an attempt to escalate drama and conflict.

- Helping students develop their awareness alone will save a great deal of suffering for all parties over time.

2. Tell What’s Bothering You

- When each participant is ready to put energy into listening and problem solving and is no longer acting out of the defensive pain reaction, they are ready to enter into a process of communication.

- Nevertheless, if the words used imply blame, attack, or indictment, not only is it likely that these are communicating the participant’s pain; it will probably trigger the other participant’s defensive reaction.

- The result will be an escalation of pain as each participant engages in a pain frenzy.

- On the surface, this may appear as communication, but in reality, it is simply people hooking one another to their inner pain mechanisms and ego defenses.

- This is what goes on in most arguments.

- The language in the participants’ communication at this stage needs to work to offer information and clarity rather than blame.

- A good technique for accomplishing this is the use of I-STATEMENTS phrases such as “I was waiting my turn and it seemed to me that you stepped in front of me,” or “What I heard you say was ‘I am a fool’ and I did not think it was funny and I did not appreciate it.”

- Drew (2002) recommends that when making I-statements, it is important to avoid put-downs, guilt trips, sarcasm, or negative body language.

- The statements need to simply report information and one’s experience.

- It is important to remind participants that both events and feelings are useful information at this stage.

- Information contributes to solutions, whereas blame, attacks, and victim language contribute to loss.

- This early step requires a great deal of trust on the part of the participants.

- They will be tempted to give in to a competitive win-lose mentality.

- In the early stages of facilitating this process, you will be required to provide a great deal of encouragement to your students to trust the process and their classmates.

3. Each Person Restates What He or She Heard the Other Person Say

- When both participants are required to restate what they heard the other say, they bring clarity and empathy into the process.

- Each is important.

- If there is no clarity, there can be little understanding, and solutions will likely be superficial.

- If there is no empathy, the opportunity for growth is lost.

- It is a sign that participants do not sincerely desire a win-win outcome.

- Successfully restating another’s words shows an effort to come out of one’s narrow point of view into a place of shared understanding.

4. Take Responsibility

- Participants in the process must realize that blaming and faulting are counterproductive and avoid them.

- Blame is external and past-oriented; responsibility is internal and present to future-oriented.

- A conflict resolution process is an effective tool to promote an internal locus of control and a consequent success psychology.

- Encourage participants to embrace the attitude that they want to see what each can do to make things better in the future.

- This is in direct contrast to the attitude characterized by the statements;

- It is not my fault or

- It is your fault.

5. Brainstorm Solutions and Come Up with One That Satisfies All Parties

- Drew (2002) suggests that resolving conflict is a creative act and that there are many solutions to any single problem.

- Participants quickly learn that conflict resolution is not about getting someone in trouble or deciding who is at fault.

- They are about how to make life better in the future.

- Sometimes this is a matter of compromise, sometimes it is a matter of finding a new and better way, and sometimes it is about one person realizing the need to change a behavior pattern.

- The conflict resolution process should be part of the social contract, but this does not imply that consequences for contract violations are ignored.

6. Affirm, Forgive, or Thank

- After a solution is agreed on, help participants develop the habit of shaking hands, thanking one another, and forgiving one another.

- Forgiveness and gratitude are powerful for closing the process.

- These signify that what was most important about this conflict resolution process was that everyone grew.

- And that the relationship was worth the effort it took to overcome the natural tendency to fight or withdraw.

Every time the students successfully execute this conflict resolution process, their skills for dealing with conflict grow.

If they can learn when they are young to recognize their defensive pain-driven mental reaction, become responsible for their actions, and forgive and move on, they will have acquired skills that are as valuable as anything else they will learn in school.

The conflict resolution process serves to promote students’ psychology of success.

Win-win conflict resolution skills promote each of these factors:

- internal locus of control,

- acceptance and belonging,

- a growth-oriented orientation to learning.

The process can be a powerful tool in the development of a more responsible approach to problems within the class.

PEER MEDIATION

When the involved parties cannot resolve conflict by using conflict resolution skills, it can be effective to enlist the help of a peer mediator.

In a peer mediation program, third-party students support their schoolmates in solving problems.

These can be problems in or out of the classroom.

The peer mediator can be any uninvolved student, but in many programs, students are given special training to be peacemakers.

Using students rather than adults to resolve conflict offers several advantages.

- It is empowering to all parties.

- Students learn that conflict is a matter to be solved with a given set of skills, not simply misbehavior.

- They learn to empathize with others’ struggles, pain, and ego attachments.

- It is much easier to help someone else look at a problem with a broad perspective than to do it oneself.

- When we see a pattern in another, we can better understand that same tendency within us.

- It puts students with strong empathetic and personal skills in positions where those skills are used for the benefit of the whole.

- Conversely, it puts those with previously underdeveloped empathy skills in a position to work on them.

The mediator should help the participants:

- Describe what they want

- Describe how they feel

- Describe the reasons for these wants and feelings

- Consider the perspective of others and summarize his or her understanding of what the other person wants

- Generate options for a mutually acceptable solution.

- Select one of the options that both parties can live with

- Make a record of the mediation

POWER STRUGGLES

- As we examine the idea of power struggle situations among students, keep in mind that you are working within the social contract or a policy framework.

- In many cases, what is occurring during a power struggle is the students’ testing the integrity of the social contract or school policy.

- They are, in essence, rejecting the class agreement.

- When a student is openly defiant, you are naturally going to feel angry and offended, and the tendency (encouraged by your defensive pain reaction) is to exert your power and show the student who is in charge.

- While this may feel satisfying in the moment, it produces several undesirable effects:

Engagement in a power struggle.

- There is no power struggle until you buy into the challenge.

- Losing sight of the point.

- The point is that the student is to be responsible and fulfill his or her agreed-upon commitment to the contract or school policy.

- Sending a message to the other students that the teacher can get hooked into a power struggle.

- Sending the message to the other students that when a student says no to the contract, he or she is given only short-term pain and not held responsible in a meaningful manner.

- What do you do to address level II cases in which a student challenges you, other than to react unconsciously to the personal offense?

Dealing with a Power Struggle

Curwin and Mendler (1986) offer seven steps to success when confronted by a student who attempts to engage in a power struggle:

1. Do not manufacture power struggles by the way you teach.

- By and large, power struggles are a result of a student’s attempt to satisfy an unmet need.

- Students who feel a sense of power and control, are making progress toward their goals, are supported by the teacher, have avenues to share concerns, and are given choices and not backed into corners by harsh directives will be much less likely to feel the need to engage the teacher in a power struggle.

2. Move into a private encounter.

- If the encounter begins publicly, quickly move it into a private, one-to-one interaction.

- A public stage will put students in a position where they must defend their image, and put you in a position in which you feel the need to demonstrate your power.

3. Avoid being hooked by the student.

- If the student tries to hook you in by making you feel guilty or responsible for his or her inappropriate behavior, ignore the hook and give the responsibility back to the student.

- A hook is intended to shift the focus externally to you or some other factor.

- The student is acting to shift blame and pull you in.

- If you become drawn in on a personal level, the student is in control.

4. Calmly acknowledge the power struggle.

- It is counterproductive to show anger or flaunting your strength.

- Instead, calmly acknowledge that things appear to be heading toward a power struggle, which would surely make any eventual outcome worse.

- Ask the student to consider how the situation could end up in a win-win scenario.

5. Validate the student’s feelings and concerns.

- Use phrases such as, “I understand your feeling the way you do, but that does not excuse what you did,” or “Those feelings make sense; I can see why you think that, but…”

- Feelings are important and valued, but they are beside the point.

- Throughout the process, project an unconditional positive regard for the student.

- You understand the student’s feelings and concerns, but at the same time maintain a clear understanding that he or she is accountable.

- If you become negative, the student will lose sight that the intervention is about his or her responsibility and see it as a punishment that is coming from an external agent.

6. Keep the focus on the student’s choice, and simply state the consequence.

- No matter what hook the student tries to use, keep the focus on the fact that the student chose to violate the rule or social contract

- I understand that you feel this is unfair, but you chose to do this.

- The consequence we decided on for that is…

- The act was the student’s choice.

- Therefore, the student must accept responsibility.

- If the student does not accept the logical or agreed-on consequence, he or she can choose to accept a more significant consequence, such as losing the opportunity to be present for part of the class or activity.

- Calmly repeating the agreement can reinforce the point to the student that he or she needs to make a choice or take responsible action.

- The rest of the conversation is secondary.

- Be careful not to badger the student.

- A calm or encouraging affect can be effective; aggressiveness will be counterproductive.

- There is no need to escalate or act out your power.

- You already have the very real power of the social contract and your rights as a teacher.

7. Put your emotional energy into constructive matters.

- After you have communicated the choices, it is not useful to dwell on the student’s behavior.

- There is no need to hover or pressure the student.

- Shift your attention back to your teaching.

- Model constructive, rational, positive behavior.

REFERENCES

- Bluestein, J. (1999). Twenty-first-century discipline. Torrance, CA: Fearon.

- Curwin, R., & Mendler, A. (1986). Discipline with dignity. Alexandria, VA: ACSD Press.

- Drew, N. (2002). Hope and healing: Peaceful parenting in an uncertain world. New York: Citadel Press.

- Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. (1999). Learning together and alone: Cooperative, competitive, and individualistic learning (4th ed.). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Join Enlighten Knowledge WhatsApp platform.

Join Enlighten Knowledge Telegram platform.

Follow our:

FACEBOOK PAGE.